Most CEOs believe they hold high standards, and are always pushing to make things better. Yet more often than not, companies face the same issues over and over again. What leads to this dynamic? In the short piece below, Jeff shines a spotlight on a simple yet typically hidden part of how executives think, and how understanding it can help you make sense of recurring issues in your business.

THINK

In this week’s sensemaker we’re offering an audio version in addition to the write-up below.

I was a philosophy major. Steve Martin said, “you take just enough philosophy in college to screw you up for the rest of your life.” Imagine the damage to a philosophy major. After 3 years of eating logic pretzels with little nutritional value, I decided that, to live a good life, I needed to ask myself two questions every day. And while I haven’t kept that up every day, I have asked myself these questions unrelentingly for the past 34 years:

- Do I want to improve?

- How will I measure myself?

Said another way:

- Get better or stay the same?

- Compare to what was or what could be?

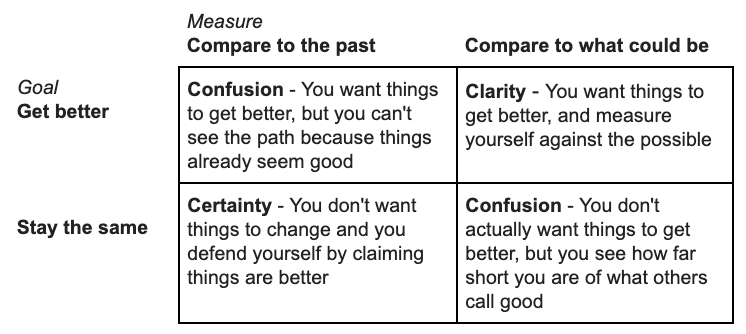

As time progressed, I saw that this made for a cool 2×2 I could use to understand how to navigate many situations. In the bottom left-hand corner would be “stay the same and compare to the past,” and in the upper right-hand corner would be “get better and compare to what could be.”

For instance, using Talentism’s 3C model, you can see that the lower left-hand corner would be “certainty”, the upper right would be “clarity,” and the other boxes would be “confusion.”

I was reminded of this 2×2 the other day when I was speaking with a CEO who was exploring a problem they were experiencing. They told me the business wasn’t achieving its goals, and they were surprised because things were so much better than they had been. I asked for the specific problem they were experiencing. They said they had found errors in some of their company’s marketing materials and when they raised the issue with their team, the team explained that the person responsible for those materials was overwhelmed, and that mistakes were inevitable. The CEO said this didn’t feel right to them, so they came to me as a coach, asking for my help turning their confusion into clarity.

I explained that before I would investigate the problem itself, I wanted to get in sync on the 2×2. Did they want to constantly improve? Yes, they replied. Do you want to measure your progress against where you were last year, or what you think great looks like? They struggled to answer that but eventually landed on “against last year.”

We then had the root of the confusion. They aspired to have great marketing materials. But when they went to explain why the mistakes were important to fix, the team’s argument of “better than last year” made sense. The mistake didn’t make sense, but the rationale for the mistake did. Thus confusion.

This self-awareness was important for them. The CEO realized that years of underwhelming business performance was rooted in this confusion. The desire was high but the standards were low. It’s a terrible combination, because it was leading the CEO to question everything but accept excuses instead of helping make things better. People felt micro-managed but nothing got better.

I can’t convince anyone to be in one box versus another. The most important thing is to know which box you are in, ensure that opinion is validated by evidence and people who care about you, and then accept there are consequences for any box you are in. As a person in the “constantly improve and compare to what could be” box, I can tell you I am frequently dissatisfied with myself and my performance. This doesn’t tend to make me the most charming fellow to be around. Everything has its price.

But if you aren’t in the upper left box, understand that you are at a strategic disadvantage to every company with a leader who is.

REFLECT

- Consider how you frame problems in your business. Are you focused more on patching holes, or constantly improving?

- Look at how you’ve allocated your time and attention relative to those problems. Is your answer to the previous question really true?

- How do you currently measure your progress against your goals?

- What do you do when you fall short of your goals?

- What does your answer to the above tell you about your underlying relationship to improvement?

TRY

- Pick an area in your business where you haven’t seen the progress you want

- Review how you’ve tried to solve the problem so far

- Based on what you’ve done, (or not done), how would an outside person evaluate how much you genuinely care about making it better?

- If it looks like you don’t actually care about getting better, consider whether someone else should own the goal

- If you genuinely do want to get better – write down what good would look like in the area in question

- List all of your excuses for not having achieved the goal so far

- Review the excuses from the perspective of “what good looks like” – do the excuses actually make sense? Note any assumptions or fears that come up while reviewing the list and comparing them to what good looks like

- Review the current game plan with anyone else involved in achieving the goal. If you switch the frame to “what good looks like” and acknowledge any fears or assumptions getting in the way, do any other paths to the goal emerge?

- Put a few of these experiments into place, and track if they make a difference.