When I have bad days (an unfortunately more frequent occurrence during COVID-19), the causes may be different, but the perspective, ultimately, always ends up the same; insufficient, overwhelmed, and, blind to the quality of relationships in my life, alone. I know I’m not the only one. With the privilege of hearing the private worlds of so many extraordinary people, it’s an all too common sentiment—that it all rests on our shoulders; that we are the only ones who will end up taking care of our needs; that we cannot rely on others; that the complexity of the world is too much to make sense of; that we, as individuals, are simply not up to the task.

When it comes to that last line at least, it’s true. The world IS too complex for any one human to make sense of productively. And I don’t just mean the big abstract world—the world of ecological destruction and accelerating technological disruption and social injustices that seem too complex for individual agency to matter. All that may be the case, but I also mean “the world” more intimately, that our day-to-day lives and cognition, our most basic notions of meaning, self, and survival, are inseparable from others. And that it is the acculturated reflex of going it alone—and designing our companies from that place—that limits our potential.

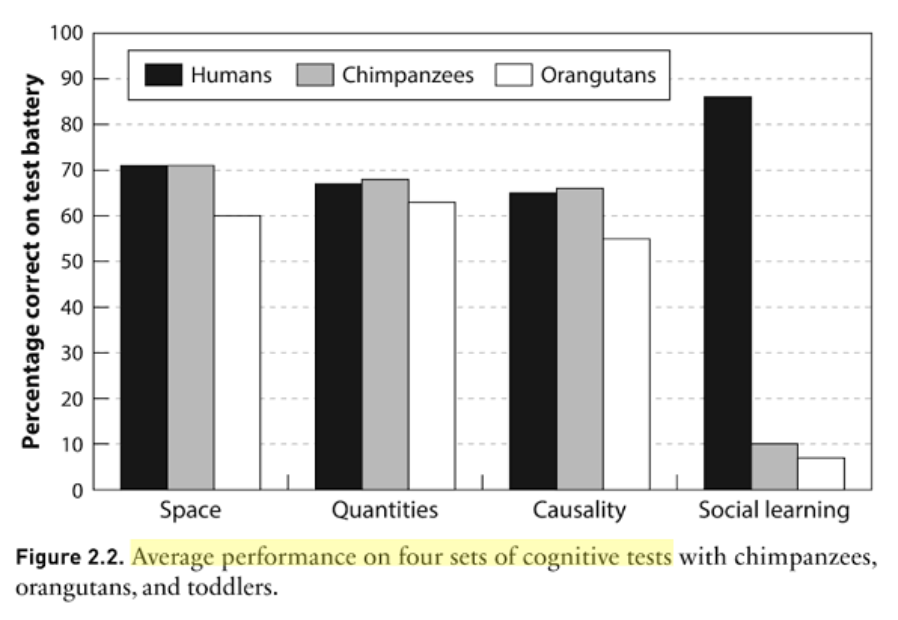

As Joseph Henrich describes in his brilliant book The Secret of Our Success, human evolution, even at the level of our individual physiology, is inseparable from the evolution of culture. Our short, weak digestive systems are predicated on cooking (in turn predicated on fire) and deep knowledge of how to process local flora and fauna, our vaunted “endurance hunting strategy” of simply out-sweating prey over long distances predicated on the ability to carry water. Yet these hunter-gatherer basics are unfathomably difficult for an individual to reconstruct, as many European explorers discovered when dying of starvation in lands the locals considered overflowing and abundant. We inherit the accumulated learnings of those before us, and in turn, contribute our own bit of sensemaking to that collective as we go out to solve the issues of our own day. That ability to inherit and transmit, to fiddle and imitate, to use our “big brains” not to figure it all out on our own, but to combine into the vastly larger brain of our shared cognition, is, according to Henrich at least, the primary driver of human evolutionary success.

While our modern, user-experience-centered society may paint an illusion otherwise, our reliance on others increases with complexity. Without going to Wikipedia, can you explain what electricity is, or how to harness it? How our immune systems work? How to treat disease, or birth a child, or grow and distribute food? Hell, how to make a fork? We are embedded in a massive, unprocessable, complex web of interactions and experimentations and collective knowledge nearly all of which is foundational to our survival and almost entirely hidden from view. COVID-19 throws this into unusually sharp relief; this past year for me has been a crash course in epidemiology, sociology, governance, complex systems and psychology—and the more I learn, the more I uncover how little I know.

For some of you, wiser than me, the sheer hubris involved in thinking we can figure it all out by ourselves is immediately obvious. Yet “smart” has long been a foundational element of my identity, and “smart” has always meant something about me as an individual: solo performance on tests (no sharing answers!), or as I entered the workforce, my ability to generate unique insights or drive results. From what I see working with many companies and leaders, most of us behave this way, at least around whatever is core to our identity. For some it’s “smart,” for others “commercial,” or “strategic,” or “creative,” or “driven,” always, in the end, a story about us as individuals and how our individual qualities make us worthy, or not.

This is one of the paradoxes of being human; we are not genetically identical like ants, nor solo survivors like pumas, meaning our success depends both on the collective intelligence of the group and our relative status within it, two drives that can often find themselves at odds. Currently our systems and culture seem to tilt toward the latter; a story that it is not great teams that rise to challenges, but individual heroes. We say we want team players, but reward those who take the credit. We recognize that science is a collective enterprise, yet focus on Nobel winners and splashy publishing records. We know that startup success is dependent on people working together toward a shared vision, yet talk much more about Jeff Bezos than the Amazon team.

There’s something beautiful to me in this tension, and I cannot imagine separating the individual drive for excellence and all the good that comes with it from the fiction of individuality itself. The history of societies that try to erase the individual look in most cases much more brutal to me than our current society’s tilt toward individuals as the fundamental unit of account. But if we’re serious about succeeding in the face of complexity—and if you’re a business leader, you’ll need to be if you want to stay in the game—then we have to learn to integrate this polarity of individual striving and collective success. This is already well established by the research on teams; as Google found in its landmark Project Aristotle study, team output was a function of effective group norms, not the strengths of the individuals involved. While innovation has almost always been a team sport, the internet has thrown this dynamic into overdrive; coordinated networks of collective sensemaking—Wikipedia, Stack Overflow, and increasingly AI-intermediated big-data pools have taken on the mantle of knowledge intermediation and distribution from heroic individuals figuring it all out on their own. The past two decades have seen an explosion of interest in innovation ecosystems—there’s a reason why Silicon Valley has held onto its cachet even beyond its most successful members. Yet our paradigm for leadership, and many of our own assumptions about what it means to succeed, remains rooted in the story of the lonely hero facing off against the world.

As an individual trying to make sense of the world and contribute, I’ve seen the key to this integration show up in the humility to recognize that my own sensemaking and output (and mental health) is fundamentally bigger than me. If our success, especially in the face of change, ultimately boils down to our ability to effectively coordinate and engage our collective sensemaking, then it follows that the key question for us in the face of obstacles is not “what do I need to do?” but “how do I best contribute to an effective team and get the help I need to cover my blind spots?” In other words, perhaps unsurprisingly to frequent readers, my answer is investing in clarity.

Why clarity? As we’ve discussed in prior Sensemakers, effectively transforming confusion into learning, instead of retrenching into protective narratives, is brutally hard, especially for an individual. It requires us to expand our perspective in moments where our biology is often telling us to narrow it. Under threat, the very parts of our brain needed to step back and consider a situation are almost entirely offline. Sure, we can do this on our own up to a certain point, provided our curiosity outstrips our fear. But very, very few people are capable of doing it consistently for themselves in the face of significant or prolonged confusion. Even fewer people can discard the new certainty narratives they form without outside help. Not only can others help us sort through what’s going on and reorient, but some research suggests we may directly cue our nervous systems off of each other, felt as some people having a “calming presence.” It’s not simply that it’s helpful for us to have access to sensemaking from others, it’s literally a requirement for learning at a certain level of trigger and complexity.

That is why every group of humans on earth has had many people informally and formally helping others make sense of what they cannot understand. Nearly all of us try to do this in some way for our families, our friends, our coworkers (with varying degrees of success). Some societies have formal roles for this: teachers and shamans, chieftains and priestesses, therapists and managers. Everyone I know who has succeeded at something great in life points to a number of such people in their lives: the teacher who saw the potential in their acting out in school, the rabbi who helped keep their marriage together, the boss who helped them express their real gifts in their work. It is nearly impossible for us to navigate well the vast “blooming, buzzing confusion” of life without it.

For this reason, I get wary of the parade of articles pushing individual mindfulness/personal growth as a response to the current chaos. It’s not that those tools aren’t valuable (they are). It’s that they miss, in looking to the singular mind, the extraordinary capacity we have when we’re there for each other. I’ve been down the rabbit hole of systems design and internal reckoning to try to make of myself something that felt commensurate to the uncomputable scale of the challenges we face, and my own inability to make sense of them in how I lived my life. The path to self-sufficient mastery dead-ends. Everyone I know, myself included, has faced some deep crisis in discovering some part of the world that did not and does not seem to fit how they thought things worked. In some cases it’s the familiar trio of old age, sickness, and death. For others, professional upheavals, great failures, or whiplash from some of the threads explored earlier in this piece. What I have seen consistently is that those who have grown from those moments are those who did so with support from others. With people who could hold faith for what they could not yet imagine, and held them to the highest standard of themselves. With people who cared for them and held them with compassion. With people who, above all, helped them make sense of what was going on.

There’s much more to say about all this—per the theme of this writeup, the idea of collective sensemaking itself is bigger than any one of us can singularly articulate. There’s big questions of social and economic structures and deliberately developmental cultures, of collective action problems and the role of technology in shaping network behavior for better and worse. What I’ll end this piece with is the simple injunction that has helped me through challenges, even if in the moment it feels hard to believe. You don’t have to do it alone. In fact, you can’t. So start thinking about how to make the most of our birthright as a species—that our big brains aren’t there to hold all the knowledge in the world, but to help us make sense of it with others. Start identifying who you can rely on, and for what. Build the trust and enterprise clarity you need to engage with them well in the face of the unknown. And above all, try to see your own limits not as a private shame, but as the spaces that enable others to join you in the jigsaw of creation. Being human is inescapably confusing, but it doesn’t have to be lonely.

REFLECT

-

Where in your life are you attached to doing it all yourself? What outputs trigger the biggest spikes of pride and shame?

-

When solving a problem, do you usually start by trying to figure it out yourself, or determining who else needs to get involved? Why?

-

Who do you go to for help? With what? Are there areas you feel hesitant to seek help? Why?

TRY

- Pick a particularly tough challenge you’ve been struggling with—could be about work or your personal life.

- Take a moment, without judgement if you can, to reflect on everything you don’t know about the problem and your own limits on executing against it.

- Create a list of everyone who might be able to help. This may be people who could help personally, but it could also be experts whose perspective you can seek via other mediums.

- Reach out to five of them. Describe the problem, your own limits when it comes to solving it, and why you’re seeking their perspective in particular.

- Track outcomes, both in terms of solutions and how you feel. How was this the same or different from how you usually go about solving problems?