Of the many challenges that our clients encounter, a persistent one is the frustration that founders and leaders experience when they attempt to move from “doing the thing” themselves, to enabling others to execute. In some cases our clients are perplexed by how difficult this is. In others, they don’t even realize how much their inability to do this is impacting their teams until we begin to probe. What’s the cause of this?

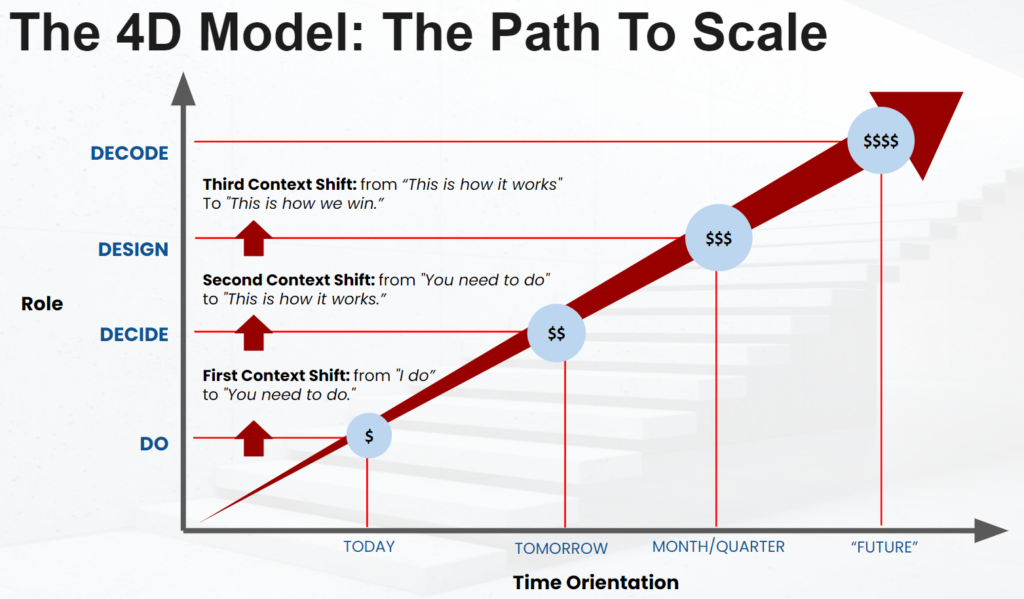

At Talentism we use our “4D Model” to help leaders understand their evolving role, what makes evolving so difficult, and how to design for it with more awareness of their own skills and blind spots. The roles below are how your time is spent.

- Do: You do the work to accomplish the goals. The limit to growth is your time: one person can only do so much in a day.

- Decide: You decide who does what. The limit to growth is your attention: there is a cap on how many projects one person can delegate, and a limit on how many people an individual can effectively delegate to.

- Design: You design the roles, structures and processes that accomplish goals. The limit to growth is an individual’s ability to deal with systematic complexity. For example, someone may excel at designing processes, but struggle to share the updated process and expectations with relevant stakeholders.

- Decode: You decode where the market is going and bring those insights to your team. There is no limit to growth.

While not completely linear, this complexity typically balloons as organizations grow. As is true for so much of our work, the challenge of these transitions is rooted in the context.

We frequently see leaders who are great at seeing the future (Decode), and have impressive capacity for getting things done (Do). Yet often they aren’t inclined to Design or Decide, either because those stages require an operational rigor and expertise that super Decoders and Doers don’t possess, or because they haven’t had the opportunity and necessity to practice. The result is that as companies grow and become more complex, those leaders create misdirection, confused priorities, and decreased productivity.

To start solving for these gaps at your organization, gather evidence of where leaders operate most effectively, and compare this to what the scope of their role necessitates. For example, people who are systems oriented may think excellently about processes, with a blind spot for how people fit into the design; this can result in a company with robust systems and processes that few people adhere to because they simply aren’t aware of expectations. The reverse can also be true: individuals who are excellent at designing for and delegating to people, may create confusion in role responsibility when they do this without adhering to existing processes.

This exercise should illustrate what’s missing, and where people’s strengths can be deployed to fill in.