This week, we continue our exploration of the New Business Playbook (NBP), the mental reference guide that today’s business leaders must use to confront today’s business realities in order to achieve their goals. In previous posts, we have discussed how the NBP thinks about vision, strategy, design, and jobs very differently than the Old Business Playbook (OBP).

But now it’s that time when things gets real, when the rubber hits the road. It’s time to move from vision statements on paper and boxes in an org design to filling those boxes with flesh and blood people who will ultimately achieve—or fail to achieve—the organization’s vision.

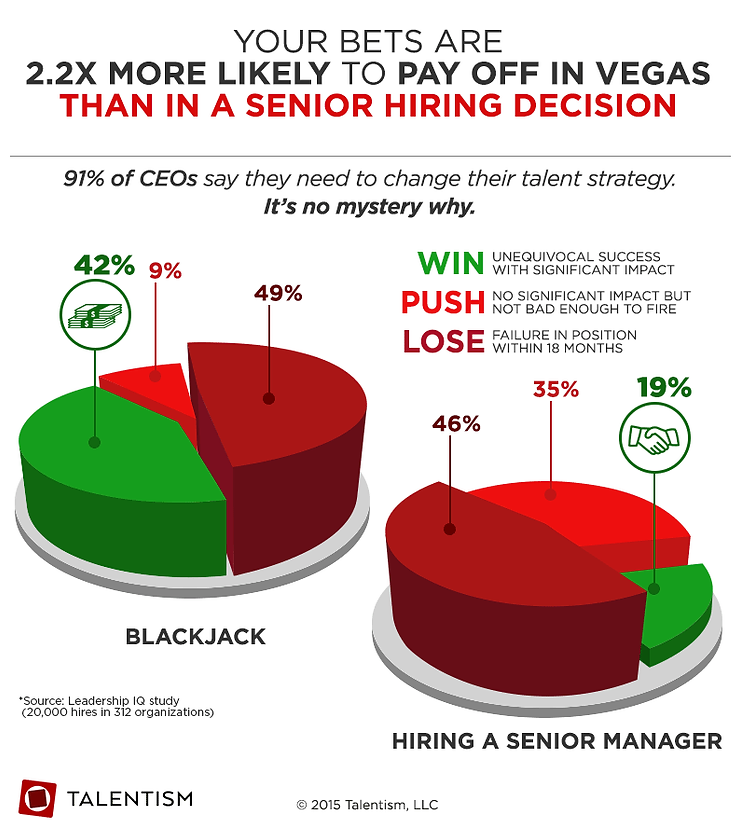

Most managers intuitively know that hiring people is one of the most important decisions they can make. Yet the practice of recruiting, particularly for senior hires, has a dismal track record in almost every industry. A Leadership IQ study of 20,000 hires in 312 organizations found that 46% of newly-hired employees will fail within 18 months, while only 19% will achieve unequivocal success. This means that a hand of Blackjack is 2.2x more likely to pay off than a hiring decision.

This should be deeply puzzling. Year after year, in industry after industry, businesses are failing miserably at one of their most important tasks. Yet nothing changes. Recruiting went from “help wanted” signs and newspaper ads, to professional search firms, monster.com and LinkedIn. Companies have experimented with case interviews, behavioral interviews, group discussions, and computerized testing. But the results have stubbornly stayed the same. We ourselves have personally spent tens of millions of dollars at large businesses on failed recruiting.

The root of the problem is not where companies are looking for people or how they are assessing them, though both those things also end up being problematic. The problem starts because most organizations most of the time are looking for the wrong thing.

We’ve all seen and perhaps written our share of “job descriptions”—those ubiquitous denizens of corporate recruiting sites and employment marketplaces. They list the responsibilities of the role and specify the qualifications of the ideal candidate. The specifications rely on a set of assumptions from the OBP that are so ingrained in our business psyche that we scarcely notice they are there. But these assumptions are wrong, with the disastrous consequences we experience in our recruiting outcomes.

The basic assumption made in current recruiting practice is that the person best suited for a job is the person with the most expertise (i.e. knowledge and skills) and the highest motivation. It relies on classic OBP thinking that treats people as interchangeable parts in a mass-production machine. The best person to turn a crank at a particular position in the assembly line is the person who has studied that specific crank, practiced turning it before, and can be motivated to turn it faster.

Crank-turning jobs have all but disappeared, particularly in more developed economies. But the OBP thinking lingers on in the way we recruit today for jobs and conditions that couldn’t even be imagined when the thinking was developed. Job specifications are full of phrases like “requires an MBA” or “minimum of 5 years experience in enterprise software sales” or “knowledge of SAS a plus” (do you have the right expertise) and other phrases like “proactive self-starter” or “takes initiative” (do you have the right motivation). This framework of hiring for expertise and motivation is nearly universal.

The problem is that a person’s current expertise and past evidence of motivation are just not very good predictors of future performance. Today’s world is changing at a whirlwind pace in unpredictable ways. Knowledge and skills are obsolete almost as soon as they are acquired, and the contexts that made a person motivated and productive in the past will not automatically be present in a new place and time.

But these contexts are the real determinants of an employee’s success and failure. This has always been true. In the world of the OBP, contexts didn’t change much for a particular crank-turning job from place to place and over time. So job-specific expertise and demonstrated motivation in the job were reasonable proxies for what is required for future success in that job.

That is no longer true. The NBP states that you must hire people who will thrive in the context that is likely to be present in the future in your specific organization. People who are optimally suited for that context will constantly learn new knowledge and skills required, work with creativity and resourcefulness, and be motivated to succeed. People who are not suited to the context will most likely fail regardless of their existing expertise and prior successes.

So what is context? It is a set of environmental conditions that businesses operate in that strongly determine both the likelihood of success of individual employees and the likelihood of the business to achieve particular goals. The two most important contexts are culture and work. Culture is people’s beliefs about acceptable behaviors, which are leading indicators of success. Work is people’s beliefs about acceptable outcomes, which are lagging indicators of success. There are other less important contexts like predictability of events and design of responsibilities. But culture and work are the most critical components of the context that determines who will succeed and fail.

When an individual is suited for a context, they regularly enter what is known as a flow state. Think of a time when you were so absorbed in work that you lost track of time and where you were. You felt like you were firing on all cylinders, like you saw problems clearly and knew exactly what to do about it. You experienced feelings of focus, enthusiasm and curiosity. If you were working with a team it is like they were reading your mind, like you could “pass the ball” to them and they would just be there. That is a flow state. It’s an actual psychological state of “optimal experience”. It is the highest, best version of your work self: clear, quick, sharp, creative, agile.

Conversely, in the wrong context, people regularly experience threat states. Think of a time when you were really anxious or scared. Perhaps you felt lost or confused, or you couldn’t quite get a hold of your thoughts. You experienced feelings of fear, dread and passivity. No matter how you tried to discipline your thinking, your mind seemed to wander back to your worry or anxiety. This is a threat state. Threat is when your performance is at its worst: when you literally can’t calm yourself and think straight, and your higher order thinking literally shuts down.

Everyone has flow and threat contexts. And they are different for everyone. The secret to recruiting success, according to the NBP, is to find people whose performance contexts match those of the organization. Fit with the culture and work beliefs that emerge in an organization—or even better are consciously designed in the way we advocate through Talent Architecture—is by far the biggest determinant of success. This doesn’t mean you can’t factor in current knowledge and skills, but those are secondary.

Let’s look at two companies that are leaders in the consumer electronic device industry and who make competing products: Samsung and Apple. Samsung is a company that is focused on relentless growth and market dominance. It’s public “Vision 2020” specifies a target of $400 billion revenue and becoming one of the world’s top five brands by 2020. Internal documents included in patent trials show that “beating Apple is #1 priority”. By contrast, Apple is a company that is focused on innovation. It was shaped by Steve Jobs, a man who wanted to “make a dent in the universe” through beautiful designs. Design chief Jonathan Ive once said, “Our goal absolutely at Apple is not to make money.” Competitors rarely come up in discourse.

That doesn’t mean Samsung can’t innovate and Apple can’t grow—they both clearly have. But the culture and work contexts that exist in each company are completely different. How people interact, what drives improvement, how standards are defined, how success is recognized—to take some examples—are all different. So the kinds of people who will succeed in one company are not the kinds of people who will succeed in the other. This should be the primary consideration for hiring.

This is a fundamental shift in approach to recruiting. It requires changing how you specify requirements for jobs, where you look for candidates (hint: not just in close competitors and elite colleges), how you assess applicants, and how you onboard and integrate new hires.

But without this shift, businesses will continue with the same costly recruiting practices that have yielded horrible results and simply hope for better results next time. And that, as Einstein said, is insanity.