You got five apes in a cage. You got a banana hanging by a string in the middle of the cage; you got some stairs going to the banana. Now pretty soon, one of those apes is going to go for the banana, and as soon as he hits the stairs you take a hose and you spray all five apes with freezing cold water for five minutes.

Now, some time passes and pretty soon one of the apes is going to make the same attempt with the same result: all five apes get sprayed with the cold water.

Turn off the cold water; you never use it again. One of the apes is going to go for the banana, he hits the stairs; the other four apes pounce on him and beat the shit out of him, right? OK, understandable. Now you replace one of those original apes with a new ape. After a while that new ape, he’s going to spy that banana, and when he goes to the stairs the other four apes are going to jump on him and beat the shit out of him, right?

Now, time passes, you replace another one of the original apes with a new ape. The new ape is gonna go for the banana—the other four apes beat the shit out of him, right? Including the first new ape who has no idea why he’s so enthusiastically beating the shit out of this poor guy, nor why he, himself, had the shit beat out of him.

Now you keep replacing these original apes with new apes until finally you have the cage filled with five apes who have never had the freezing cold water sprayed on them, and nevertheless not one of the apes will ever attempt to climb those stairs again. Why not? Because that’s the way it’s always been done around here.

—President Jackson Evans, played by Jeff Bridges, in The Contender

Herb Shows the Luv

The Dallas Sportatorium was the embodiment of a rough night out. Little more than a tin barn with dirt floors, it smelled of old beer and cigarettes, and it was muggy as hell. The ramshackle bleachers seemed like a preface to a class action, though they didn’t seat many lawyers. For decades, the Sportatorium was the heart of pro wrestling in Texas. Superstars such as Booker T, Shawn Michaels, and “Stone Cold” Steve Austin graced its squared circle. And, of course, Southwest Airlines Chairman and CEO Herb Kelleher.

Every wrestler needs entrance music. When Kelleher entered the musty old building in March 1994, it was to “Gonna Fly Now”, better known as the theme from Rocky. He strode confidently down the aisle towards the ring, situated between a man in a spiky black wig and another wearing a strap of Wild Turkey mini bottles. Kelleher himself was adorned in a robe with “Smokin’ Herb” inscribed on the back, and a cigarette appropriately clenched between his teeth. Jack LaLanne he wasn’t, but the assembled crowd loved it. As he slipped between the ropes of the ring and took his seat on a large padded chair, the crowd began chanting, “Herb! Herb! Herb!”

It was even more shaggy and campy than the wrestling events it was emulating. Ostensibly, the event was a best-two-out-of-three arm wrestling match between Kelleher and Stevens Aviation chairman Kurt Herwald that would decide whether Southwest could retain the rights to the punny slogan “Just Plane Smart”, which was a likely legal infringement on Stevens’ existing slogan, “Plane Smart”. Kelleher enjoyed a good time, and recognized a good opportunity. When Herwald suggested that they settle the matter out of court and in the ring, Kelleher jumped at it.

Welcome to the Dark Side

Herb Kelleher Way now leads into and out of Love Field, the regional airport where Southwest started back in 1971. After a few miles and a few turns, the road connects to I-75, which turns into I-45 down to Houston. Over the four hour drive the climate doesn’t change much, a little less windy and a little more humid and green, as though Houston were born of a flirtation between Dallas and New Orleans. In the center of the city, less than a mile from the freeway, stands Chevron’s Texas headquarters: 1400 Smith Street and 1500 Louisiana Street, two fifty story skyscrapers connected to each other by a circular skywalk. Back in 1992, while Herb Kelleher hopped around a wrestling ring 240 miles away, only the Smith Street tower stood, the headquarters of an emerging powerhouse in commodities trading. The other was completed ten years later, mere months after the financial collapse of its original builder and owner, Enron.

If Southwest was the only consistently profitable company in an established, hoary industry, Enron was the brand new ideas factory that no one seemed to really understand. But that didn’t stop people from wanting to be a part of it. Enron was named the most innovative company six years in a row by Fortune, and several times made the magazine’s list of “100 Best Companies to Work for in America”. Enron was transforming Houston into a commercial powerhouse as Texas Instruments had for Dallas. Analysts were certain of a bright future for the company—up until it declared bankruptcy.

The meteoric rise and stunning crash of one of the world’s most innovative companies was the brainchild of Jeff Skilling. Alternately feared and revered by throngs of Enron employees, Skilling was perhaps the man most responsible for making Enron what it was. A top scholar at Harvard Business School and the youngest person to ever make partner at McKinsey, Skilling changed the very nature of the company during his ascension to the top office, dazzling executives and analysts along the way with his sharp intelligence. He had a fiery passion for commercial innovation – it was Skilling’s idea to financialize and transform energy into something that could be traded like stocks and bonds. It not only eventually made Enron into one of the largest companies in the nation, but also changed the way energy companies were run. And Skilling wanted that level of innovation to flourish throughout the company.

What is Culture?

It seems that the business community has come to an agreement that culture is a Very Important Thing. But that’s where consensus ends. Michael Watkins in Harvard Business Review (amongst many others) observed that there are roughly as many definitions for culture as there are businesses concerned about it. “If you want to provoke a vigorous debate, start a conversation on organizational culture,” writes Watkins. “While there is universal agreement that (1) it exists, and (2) that it plays a crucial role in influencing behavior in organizations, there is little agreement on what organizational culture actually is, never mind how it influences behavior and whether it is something leaders can change.” To tackle this problem, Watkins synthesized a convoluted definition that takes an entire article to spell out. Some highlights:

- “Culture is how organizations ‘do things’.”

- “In large part, culture is a product of compensation.”

- “Organizational culture defines a jointly shared description of an organization from within.”

- “Organizational culture is the sum of values and rituals which serve as ‘glue’ to integrate the members of the organization.”

- “Organizational culture is civilization in the workplace.”

And so on. This blanket approach to defining culture is perhaps best summed up in what airbnb CEO Brian Chesky wrote when explaining the importance of culture to his employees: “Culture is a thousand things, a thousand times.” Poetic, perhaps, but not very explanatory or useful. Murky mantras like these dominate our discussion of culture, obscuring the forest with many things that probably aren’t trees. As a result, leaders are confused about what culture is and why they should care. Many ultimately give into the current convention of assuming that fun, free lunches, and casual attire are all that you have to do to create a “unique culture.”

This terrible thinking has resulted in lost productivity, miserable employees, and ultimately failed businesses. Culture is neither as cool nor as mysterious as the current chattering class make it out to be. In fact, culture forms within an organization regardless of whether anyone pays any attention to it, because culture will happen whenever people come together. Social psychologists spent several decades figuring out these dynamics, discovering how human behaviors are affected by authority, group dynamics, and autonomy. And they have come to some surprising conclusions.

It’s All About the LUV

Southwest had dubbed Kelleher’s arm wrestling match “Malice in Dallas”, and it was undeniably a publicity stunt. But it was also undeniably fun. Unlike many highly theatrical promotions, it wasn’t a cringe-inducing display of wooden apathy. Kelleher didn’t play the role of a CEO who would rather be on a golf course—he relished the attention and stagecraft of it all, playing the heel, starting fake fights, being carried out on a stretcher after his loss. (In victory, Herwald announced that he would allow Southwest to continue to use the slogan.)

Everyone else in and out of the ring loved it too. Even watching the videos now, for all of the ridiculousness, it’s infectious.

Even when the cameras weren’t rolling, Kelleher didn’t stop having fun. He loved keeping employees and competitors alike out all night, and threw elaborate costumed parties for the company on a regular basis. His sense of humor and encouragements to “Be Yourself” permeated the entire company. Southwest flight attendants in turn came to be known for their hijinks, from singing (or rapping) their safety announcements and practicing their stand-up routines to popping out of overhead bins while the passengers were finding their seats.

But for all the “Be Yourself”-infused fun, the critical parts of Southwest’s culture—the things that ultimately created success for the company—were a reflection of Kelleher in more important, more profound ways. As much as he loved shenanigans, Kelleher loved people more. ”I feel that you have to be with your employees through all their difficulties, that you have to be interested in them personally,” Kelleher once said. “They may be disappointed in their country. Even their family might not be working out the way they wish it would. But I want them to know that Southwest will always be there for them.”

Many people will roll their eyes any time “caring about your people” worms its way into the business lexicon. Such mechanical sloganeering has been an ever-present feature of corporate messaging for decades, thanks to the influence of books like Jim Collins’ Built to Last. But rarely does it seem truly sincere. “Caring about people” is one of the most abused values around, plastered by HR on hiring websites and campus presentations.

What made “caring” different at Southwest? And how did it create a culture that actually influenced behavior for the good of the business rather than simply adorning a values statement?

“When I started working for Southwest, I worked three levels below founder Herb Kelleher,” recalls Dave Ridley, who now serves as Senior Advisor to the CEO. “Within weeks, he knew my wife and children’s names, what my outside interests were, and a lot about my background. I knew within three months of going to work at Southwest that Herb would fall on a grenade for me or any member of my family. His love for people was palpable.”

Steve Lewins, a Gruntal & Co. analyst, paid close attention to Kelleher’s moves for years. ”I think Herb is brilliant, charming, cunning, and tough,” he says. “He is the sort of manager who will stay out with a mechanic in some bar until four o’clock in the morning to find out what is going on. And then he will fix whatever is wrong.”

The employees all the way down the line recognized Kelleher’s compassion as well. One pilot remarked, “I can call him almost 24 hours a day. If it’s an emergency, he will call back in 15 minutes. He is one of the inspirations for this company. He’s the guiding light. He listens to everybody. He’s unbelievable when it comes to personal etiquette. If you’ve got a problem, he cares.”

Says Ridley: “When people know that leadership cares that much about them, they’ll do remarkable things for that leader—and for the organization.”

And he’s right: the effects of management’s compassion trickles down to all levels of the company. Southwest employees are well known for the extra mile they go for flyers, leading to exceptional customer satisfaction ratings. But employee dedication comes out not just during interactions with customers. Employees are devoted enough to the airline that they routinely go beyond the strict measures of their job specifications to get better results for the airline. For example, pilots routinely assist with plane cleanup to decrease turnaround times.

This is emblematic of another aspect of Herb that was on display in “Malice”: his dedication to keeping costs low. Kelleher estimated that the event saved his company half a million dollars in legal costs, a fact he told a news crew as he was being carried from the ring on a stretcher. And for all the attention paid to customers by employees, the airline has never offered much in the way of frills, not even in-flight meals. But even this strategy is borne of genuine caring—Southwest, from the beginning, has been steadfast in its commitment to keeping ticket prices affordable, effectively democratizing the sky. The long-term commitment to quick turnarounds and excellent on-time rates are only possible with a culture that is passionate about keeping costs low and flights affordable.

That too has started at the top. When Kelleher asked for his pilots to take a 5 year pay freeze, he took a 5 year pay freeze. For other executives, Kelleher tied pay increases to his non-contract employees—if they got a 2% pay increase, the executives did too. This has resulted in the highest paid employees in the airline industry—who received raises even during economic downturns, and have never experienced a furlough—with some of the lowest paid executives. “We’re not afraid to show our people that we’re not in it for ourselves,” Kelleher said. He put his money where his mouth was, and the results showed.

And that has meant profit. Despite the fact that Southwest often competes for the lowest fares around, and despite the fact that it’s employees are paid at above-average rates, Southwest is among the most profitable airlines around. Southwest has maintained profitability every year since 1973. No other airline has come close to that streak.

Southwest has maintained this remarkable record because it gets people up and down its ranks to relentlessly focus on going the extra mile to keep customer satisfaction high and costs low. Southwest’s values, plastered all over their promotional materials, aren’t just values—they’re embodied every day by countless actions by employees. Those actions aren’t accidental. They are the result of signals generated by the leader, starting with his own behavior, and extending to how people are hired, compensated, recognized, promoted, and fired. Those signals from the top create the culture, and culture creates behavior.

Get in Line

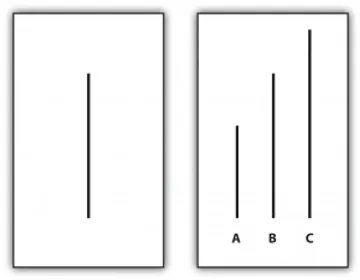

The year was 1951 and experimental psychology was establishing itself as an important academic field in postwar America. At Pennsylvania’s prestigious Swarthmore College, selected students in Solomon Asch’s laboratory were given a simple perceptual task. They were shown placards with four lines, one on the left and three on the right, and were instructed to state which line from the right grouping matched the length of the line on the left.

By all appearances, the experiment was remarkably simple. And for the first two placards, it was: each of the four participants correctly identified the correct match.

But then something strange started to happen in the third trial. Each student observed as the other three participants in the room, with assured confidence, began to simultaneously call out the same incorrect answer. This happened for 11 of the 15 remaining trials. The experiment, as the students would only later discover, was not about testing simple perception; the other three participants in the room with the student were in fact confederates, deliberately giving the same wrong answers.

Despite the obviousness of any given answer, only 25% of the students gave the correct answer for every trial. 5% went with the confederates on every answer. The rest would vacillate between conformity and fidelity to their own perceptions.

The same year Asch was discovering the pressure that individuals felt to conform to the group, social psychologist Stanley Schachter was testing how the collective responds to dissent. Groups of students were organized to discuss what to do with a juvenile delinquent. However, each group included a confederate who argued against whatever position the rest of the group took. The deviants were targeted initially with heightened levels of persuasion before, slowly, the groups gave up and disregarded their opinions. When the participants were subsequently instructed to create a student organization, the deviants were consistently relegated to the most menial tasks.

There’s a reason that groupings of self-identified non-conformists all tend to look alike. People of all backgrounds and beliefs are highly affected by an unconscious desire to conform to norms, regardless of how they’ve constructed their internal narrative about what they think is right and wrong. Even the strongest non-conformists in Asch’s experiments reported desires to go along with the group, and felt relief rather than vindication when the true intention of the experiment was revealed. And as Schachter’s experiment showed, this concern with conformity wasn’t mere paranoia. Iconoclasm has not only psychological costs, but social and economic ones as well.

It’s therefore not surprising that conformist behaviors are rampant in the workplace. When Google funded a project to discover the implications of group dynamics, they discovered:

Team members may behave in certain ways as individuals — they may chafe against authority or prefer working independently — but when they gather, the group’s norms typically override individual proclivities and encourage deference to the team.

Google’s findings are present in organizational literature as well. Studies have shown that employees are more likely to notice deviant behaviors than normative behaviors, and antisocial behaviors in employees have been shown to spread to other employees.

The group mentality underlying Southwest mirrored Kelleher’s own mentality. Encouraged by leadership and feeding off their behaviors, Southwest employees are more likely to notice and respond positively to actions that enable them carry out their work. This positive feedback loop is critical to Southwest’s turnaround time, which is heavily reliant on employees supporting each other in task completion. The signal from the leader is amplified by the group engaging in the same behaviors.

Fantastic to Fear to Failure

Sherron Watkins joined Enron in 1993, eager to be closer to home after spending years working for Metallgesellschaft in Manhattan. Enron was the only company she considered, a press darling that seemed to print money and mint millionaires. For the privilege of working there, she had taken a pay cut and a lower tier title, moving from vice president down to director. But Enron was hot, and the offer was too good to pass up. Within a few weeks of her arrival in Houston, Watkins’ old employer went under in an accounting scandal. For the first time, she was summoned to meet Enron’s golden boy: Jeff Skilling.

Skilling wanted to learn from Watkins. What had happened at Metallgesellschaft? Could the same thing happen to Enron? What safeguards could they put in place to show investors and customers alike that such a thing could never happen in Houston? Watkins, new to the company, said that MG’s problems with the balance sheet were caused by “desperate moves by desperate people.” Over a decade later, Watkins still remembered Skilling’s response: “That’s not a good answer. We could become desperate one day.”

A few months afterward in Aspen, Watkins hoped some face time would ingratiate herself to the man everyone assumed would become CEO, but she found that Skilling never “turned off”. “The man never seemed to relax,” Watkins wrote with Mimi Swartz in Power Failure: The Inside Story of The Collapse of Enron. “How could they make Enron better? he wanted to know. Whom should they hire? What else did they need to be truly great?”

Skilling’s unending passion for bettering the company found its vehicle in the company’s culture, and that started with a sense of purpose. Enron “started with a lot of people who thought they were changing the world,” notes Bethany McLean, author of the The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron. Along with chairman Ken Lay, Skilling sought to deregulate markets across the country, profoundly and sincerely believing that government interference stifled innovation. And, above all, commercial innovation lead to making more money.

Skilling’s thought that in order to be innovative, companies had to allow employees to fail. While commonplace business logic today (see Jeff Bezos’ most recent letter to Amazon shareholders), it was a departure from conventional wisdom at that time. He tried to build the company to be “loose tight”, mirroring the language of McKinsey consultant Tom Peters in In Search of Excellence, as a means of spurring innovation from the bottom while driving people to make deals from the top. Skilling strove to hire the best talent possible. Their jobs were kept fluid, allowing new recruits to move around the company to find the jobs they wanted. Both Peters’ book and McKinsey’s The War for Talent were required reading around the office. Only “A Players” were allowed to join Enron’s vaunted ranks. Skilling’s moves to increase teamwork by linking employment status to peer evaluations came straight from his alma mater’s emphasis on small groups as the optimal business unit to “liberate human potential”.

But all was not perfect in the most innovative company in the world.

83% of U.S. employees think that their employers don’t care about their opinion. At Enron it was no different. In an employee survey conducted before Wall Street saw the warning signs, Enron employees expressed confidence in their managers, but worried about “speaking out” for fear of retribution. Lay and Skilling declared this “unacceptable” and announced action to correct this pattern. Given Sherron Watkins’ earlier interactions with Skilling, it is likely he was sincere in his disgust. But Watkins herself was frequently told not to question her bosses or go over their heads by other employees. Every move felt like it could endanger her career progress.

In truth, the culture of the company was often less than constructive. Skilling’s traders were running more than the trading floor. Since most of the company’s revenues came from them, they were rewarded the most lavishly, sometimes making more per year than anyone in the executive ranks. If money was the ultimate good at Enron, traders were the moral arbiters. Their success meant that they weren’t subject to the same rules as anyone else. They were young, mostly male, arrogant, and aggressive. They worshipped Skilling, but at the same time paid him no heed when he repeatedly asked them to swear less on the trading floor. They sexually harassed women with no consequences and then blew tens of thousands of dollars at strip clubs on company cards. They took the biggest risks for the biggest rewards, and stomped on anyone in their way as a matter of course. During the California energy crisis, traders routinely made deals to increase their profits at the expense of the residents of the state, deliberately creating energy shortages that lead to rolling blackouts. And if you didn’t act like the traders, you were a loser.

“I was never comfortable on the trading floor at Enron,” reports former trader Colin Whitehead. “And if I had questions, I didn’t ask them, because I didn’t want to know the answer. I didn’t want confirmed what I suspected might be true, that what I was doing was in fact unseemly or was at least unethical if not worse.”

These behaviors might have been more easily contained if not for the fluidity of Enron’s internal labor market. Employees changed divisions frequently in search of a bigger payday. At a place like Enron, that meant the newest divisions, and the newest products, regardless of whether the employees had any relevant expertise. As Skilling ascended the corporate ladder, his abrasive acolytes began to pop up in every corner of the company.

Jeff Skilling created Enron Capital & Trade, and was the force behind Enron’s frequent reorganizations. Though he didn’t share many of the most abhorrent behaviors of the traders, and made pronouncements to mitigate them, he still enabled them. Likely, he was afraid that talented employees who had proven they could make the company money would seek opportunities on the coasts. But this fear created a ticking time bomb, doing an end around on Skilling’s careful attempts at risk mitigation.

In truth, Skilling was just as subject to group norms as anyone. In the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, student volunteers were separated into two groups, guards and prisoners. The guards soon began overreaching their authority, and the prisoners (who were free to go at any point) willingly chose to be subject to psychological and physical abuse. Head researcher Philip Zimbardo was surprised to find himself affected by the experiment as well, as he allowed the abuse of the prisoners to continue.

Skilling was similarly affected by group dynamics. Skilling thought himself risk averse, but had created a culture where risk-taking occurred regularly. That culture affected him as well. McLean writes, “[Skilling] personally approved some deals even when he was openly skeptical, especially if they were backed by one of his trusted deputies. ‘I don’t like this deal. I hate this deal!’ Skilling would announce in a meeting. Then he’d look over at the senior dealmaker backing the transaction and tell him he was getting a pass. ‘If you really want to do it, this is your silver bullet, but I’m going to hold you responsible.’” He rarely did. And because of that, Enron ended in ruin.

Skilling’s earnest belief in Enron somehow persisted past its collapse. Of the 24 people indicted and convicted for their roles in the scandal, Skilling was the only prominent figure who never invoked his Fifth Amendment rights. Instead, against his lawyer’s wishes, he argued passionately—yet ultimately unconvincingly—for his dead company’s honor. Skilling’s lawyer, as it turned out, was correct. CFO Andy Fastow, despite being the most culpable of any employee in the financial malfeasance that brought the company down, received only a six-year prison sentence by pleading the Fifth in Congress and cooperating with the authorities. Skilling received 24 years, by far the longest sentence of anyone involved.

Clayton Christensen, author of The Innovator’s Dilemma and classmate of Skilling, remembers the person he knew before the collapse. “The Skilling I knew was a good man,” Christensen recalled. “Smart, worked hard, loved his family,” Christensen was so struck by what happened to Skilling that he wrote a self-help book in response, aimed at executives working long hours in high stress positions who needed to find balance.

No one argues that Skilling wasn’t blameworthy for the collapse of his company and for the billions of dollars that evaporated out of the retirement funds of his workers. According to Watkins, Skilling was one of the main reasons for the collapse of the company, not the least of all because of the way he enabled and protected Fastow. But despite being branded as the paragon of corporate greed, Skilling’s actions don’t indicate any sort of maliciousness or prodigious selfishness.

“Skilling himself may have believed he was the moral leader humanizing business,” writes James Hoopes, author of False Prophets: The Gurus Who Created Modern Management And Why Their Ideas Are Bad For Business Today. “[Skilling’s] erratic behavior in his last few weeks at Enron”—heavy drinking, losing weight and sleep, avoiding the office, quitting the company and leaving $20 million on the table before making an anguished bid to return when it all started collapsing—“suggests less the desperation of a cornered crook than a neurotic crisis in the face of a collapsing dream castle.” But the collapsed castle lead to twenty-four convictions, and hundreds if not thousands of examples of employees engaging in morally questionable behavior.

Values Are as Values Does

The Enron Code of Ethics was devised during the company’s heyday at the behest of long time CEO Ken Lay. Banners emblazoned with its aphorisms were hung around the office, and promotional videos featuring Lay and Skilling were distributed to employees. The code states:

Respect

We treat others as we would like to be treated ourselves. We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful treatment. Ruthlessness, callousness and arrogance don’t belong here.

Integrity

We work with customers and prospects openly, honestly and sincerely. When we say we will do something, we will do it; when we say we cannot or will not do something, then we won’t do it.

Communication

We have an obligation to communicate. Here we take the time to talk with one another . . . and to listen. We believe that information is meant to move and that information moves people.

Excellence

We are satisfied with nothing less than the very best in everything we do. We will continue to raise the bar for everyone. The great fun here will be for all of us to discover just how good we can really be.

But the code of ethics is really just a list of aspirations. Enron failed to achieve most of them. Because, in reality, those aspirations were not an accurate statement of who Skilling was as a person. It wasn’t what he was like. He wasn’t an evil force attempting to bankrupt the company. He was just never going to hold others responsible for not embodying that code. That’s not who Ken Lay and Andy Fastow were. The reality of their behaviors, and the behaviors they explicitly and implicitly rewarded, didn’t match the messaging in the posters and videos.

Values and behaviors are different things. Values are a statement of what you care about. Behaviors are what you do. You can rarely predict someone’s behaviors by reading their values. And this disconnect can cause a lot of confusion. “Too many values are just words,” says Lou Gerstner, who used a tight focus on culture to turn around IBM in the ‘90s:

If the practices and processes inside a company don’t drive the execution of values, then people don’t get it. The question is, do you create a culture of behavior and action that really demonstrates those values and a reward system for those who adhere to them?

Kelleher agrees, though with a different perspective. Southwest’s value of caring is, “not a programmatic thing. It can’t be,” he says.

It has to come from the heart, not the head. If it’s programmatic, everybody will know that and say, “Hell, they’re not sincere; they don’t really care, they’re just telling us that they care.” It has to be a continuous stream of one-on-one communication, not like you sit down and say, “Boy, communication is pretty important. Let’s really communicate for the next six months and then move on to what’s really significant.” It has to be part of your fabric; it has to be something that you do really as a product of your soul.

Gerstner and Kelleher recognized that while countless companies parrot ideas such as “caring for people” or “open communication” being a critical part of their culture, such values have zero effect if they are not backed up with actions. Aspirations unaligned with behaviors create only cynicism in employees, who silently scoff at each iteration of the company’s supposed values.

Unfortunately the executive team at Enron didn’t understand this. Ken Lay could talk all day long about excellence, but he was most concerned with appearances. He hated saying no almost as much as he hated hearing bad news. Skilling, on the other hand, made his name as a risk manager. As shown by his conversations with Watkins, it wasn’t just an honorific. He spoke with his employees about risk frequently. But he cared about winning more. He valued the creative and eccentric types who would give him security and status, and he gave them free reign to be “creative.” For as much as he talked about risk, he never reigned in risky behaviors. And those who took the biggest risks got the biggest rewards in the form of bonuses and promotions. That message rang louder than any words written in a code of ethics.

Skilling was notoriously arrogant, and ignored his blind spots. He didn’t overtly tell people that it was good to engage in risky behaviors—quite the opposite. He may not have even thought that it was desirable to engage in risky behaviors. But he certainly behaved as if risk was the ultimate good. The system he set up certainty rewarded it. It was signaled in the testosterone-laced company retreats he organized for top lieutenants. It was signaled in the bonus structure that was based on closing deals rather than those deals actually being profitable for the company. It was signaled in his tacit willingness to go along with deals proposed by underlings that he himself thought were questionable. Skilling let risk become the coin of success because that is what Skilling wanted: more coins.

By focusing on the stated values at Enron, Skilling and others allowed themselves to excuse behaviors. People are powerful rationalizers; we all frequently excuse our behaviors with appeals to values, using stock phrases such as, “their hearts were in the right place.” And we see this sort of rationalization with Skilling. Though he has been branded the High Satan of corporate America, reading through the accounts it’s striking how frequently he seemed to believe his own bullshit. But it was because he believed, on an intellectual level, in the cultural values he trumpeted, and the risk management principles he set in place, that he was able to delude himself that the behaviors that came most naturally to him were in service to those values. And since he was blind to his weaknesses, his weaknesses influenced those around him. The culture simply emerged from those signals.

Shocked and Surprised

Both Kelleher and Skilling demonstrate that leaders are the primary creators and motivators of organizational culture. However a company may be structured—whether it is militaristic in its hierarchy or flatter than a pancake—at least one person has the ultimate authority to hire or fire people. They control membership in the group. In the vast majority of organizations, at least one person has the ability to promote or demote people. They control status within the group. And the authority to control membership and status has tremendous psychological power. This power means that leaders have the single greatest effect on culture—and therefore context—of how people behave.

But there are far deeper, more important, and less rational realities about the relationship between authority and behavior. This was perhaps most clearly demonstrated in the obedience studies of Stanley Milgram.

A social psychologist by training, Milgram developed his intense interest in the nature of authority through his encounters with members of his family who had survived the holocaust. In an effort to determine what could make millions of people act so callously towards their fellow man, Milgram devised a set of controversial experiments which would shock the world and drive many of his experimental subjects to tears.

The experiments started at Yale University’s Interaction Laboratory in July of 1961. Two male volunteers were led into a room by an unidentified man in a white coat. The volunteers were randomly assigned roles of “teacher” and “learner”; the learner was led into a room and attached to an electrode in view of the teacher, and then the teacher was led into another room and shown a machine that would administer an escalating series of electric shocks up to 450 volts. Teacher and learner could not see each other, but could hear each other. The stated rationale behind the experiment was to discover whether a series of electric shocks would improve or impair a learner’s ability to memorize word pairs.

In reality, only the teacher was an experimental subject—the seemingly random role assignments were in fact fixed. The learner was a confederate who did not actually receive any shocks, but played a tape of pre-recorded responses. As the voltage of the shocks escalated, so too did the recorded actor’s histrionics, up until they pretended to pass out.

Before the start of the first experiment, Milgram polled students, colleagues, and psychiatrists from the medical school; every group believed that few if any of the teachers would choose to ignore the pleas of the learner and administer all the shocks. The actual results: 65% went all the way to 450 volts, shocking an unconscious stranger with lethal levels of electricity. Subsequent variations of the experiment produced similar results.

The teachers did not proceed with blind obedience; not a single one of the original group failed to question the experiment at some point, even as the Man in the White Coat always encouraged them onward. They exhibited many signs of stress: sweating, biting their lips, trembling, laughing nervously. Many broke down completely.

Other researchers were (less literally) shocked by the results. Charles Sherman and Richard King theorized that subjects might be able to tell the experiment was a farce, and replicated it with real voltage. Legally, of course, they were unable to use humans as the recipients of the shocks. So they instead used the thing most likely to inspire empathy in the participants: cute, cuddly puppies.

Like Milgram, the voltage escalated with each subsequent shock, administered when the puppy stood in the wrong place in response to a flashed light. Unlike Milgram, the subjects could now see what they were harming. As the voltage increased, the puppies barked, leaped about, and finally howled and writhed in pain. Twenty out of twenty-six volunteers went all the way to the maximum voltage. (While Milgram had used all male subjects, Sherman and King used both men and women. Every single woman went to the maximum voltage.) Again the participants were horrified and exhibited extreme stress reactions. And again, most of them went through with it anyway.

In all the Milgram variations, there was one variable that made a significant difference to the results: the distance of the subject from the Man in the White Coat. The closer the authority figures were, the more they gently encouraged the subjects to continue with the experiment, and the more they offered to take responsibility for the subject’s actions to the gently encouraging authority figure, the more likely the subject was to continue with the experiment. Exit interviews would indicate that the subjects continued on for the “the good of science.”

In modern business, “the good of science” is easily substituted with “the good of the company.” Sherron Watkins and hundreds of others at Enron repeatedly compromised their morals for “the good of the company.” People continue to rationalize their behaviors that way every time management asks them to do something that makes them uncomfortable”, encouraged by the signals put out by the authority figure. Humanity’s obeisance towards authority runs very deep.

Consciously or unconsciously, leaders create the behavioral norms that form the basis of culture. That’s the genesis. The culture then takes on a life of its own through the dynamics of groups.

How Do We Fail to Become the People We Want to Be?

Aretaeus of Cappadocia, one of the earliest and most notable Greek physicians, wrote in the first century CE, “melancholia sufferers complain of a thousand futilities.” Even the ancients realized that those who have experienced repeated but inescapable pain may complain, but no longer try to avoid it. Modern psychiatry has put a name on this condition: learned helplessness.

It wasn’t man or ape that first helped researchers describe learned helplessness, but dogs. In 1967, University of Pennsylvania psychologist Martin Seligman beat Sheridan and King to the punch by a few years, and devised an experiment that involved shocking the animals—but instead of studying the behavior of the humans doing the shocking, Seligman was interested in the behavior of the dogs themselves.

Seligman separated two dogs and placed them in harnesses, each next to a different lever. The pair was then shocked at the same time. For one dog, the level stopped the shock for both animals; for the other dog, the lever did nothing. The dogs with the working lever learned quickly to press it as soon as the shock started. To the second dog, however, the shocks seemed to end arbitrarily.

In a follow up experiment, three groups of dogs—one which had not been shocked, one which had been shocked with a lever to cease the shock, and the third group which had been shocked without the ability to stop it—were placed in a box split in two by a low divider. One half of the box could deliver shocks, while the other was safe. The first two groups of dogs learned quickly to jump the short fence towards safety as soon as the shock started. The last group—the one that had previously been shocked without the ability to stop it—lay in the box and whined during the shock, but did not attempt to escape it. Only by physically picking up the dogs and moving them could they teach this last group to escape the shock. Treats, threats, and visual demonstrations did nothing.

Decades of research confirmed what Sherron Watkins could see all around her at Enron—many people, confused by the culture and afraid of their superiors, exhibit signs of learned helplessness in the workplace. And learned helplessness kills productivity. When Enron trader Colin Whitehead avoided asking uncomfortable questions, he not only feared the answers, but felt powerless to stop them. Sherron Watkins, acclaimed whistle blower and one of Time’s 2002 Persons of the Year, suffered from learned helplessness as well. When her boss Andy Fastow told her to forge documentation, she hoped he would forget that he asked. When a spurned client told her that Ken Lay and Jeff Skilling were the most unethical people they’d ever met and expressed contempt that she would work for them, Watkins thought of her mortgage payments and did nothing. And when she possessed evidence of some of the greatest accounting fraud in corporate history, she wrote an anonymous note to the CEO expressing concern that the company had become a risky place to work.

Culture is ultimately not just about behaviors—it’s what behaviors the employees think will be punished and rewarded. Skilling and Lay may have proclaimed until they were blue in the face that they wanted people to speak their minds, but no one believed them. Google’s investigation revealed that the most productive group dynamics featured the highest levels of psychological safety—the belief of the members that the group is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. The culture of Enron, infested with arrogance and recklessness, left no space for interpersonal risks, only financial.

Sherron Watkins is a good woman—devoted wife, mother, friend, and churchgoer. The actions of her boss Andy Fastow bothered her deeply. The way people she called her friends failed to look after hard-working people in the field who never made huge bonuses disgusted her. But for eight years she worked in a culture that was very, very confusing to her, and her ideas about what behaviors were optimal were always in doubt. She had no sense of psychological safety, with deep fears about speaking out or trying something new. The fact that she spoke up in her memo to Ken Lay was exceptionally difficult for her, and worthy of being lauded. The fact that she did so in such a limited capacity, and that she was the only one, is indicative of a culture that inhibited its own people to the core.

Cultures that send mixed messages—where the leaders don’t do what they say, and where different groups around the company have their own set of standards—end up confusing people, beating them down and leaving them in pain. The culture doesn’t make sense to them because the culture doesn’t make sense. Enron sought competitive advantage by hiring the best and the brightest. But with the culture the company had, the best and brightest couldn’t make a dime.

Culture is Everything

Culture is both the why and how: why we do what we do and how we do it. Culture exists wherever people are trying to get work done. Culture is created by all of us: by what leaders say and do; by what we believe about ourselves; by how we act; by how we are influenced by others. Ultimately culture is just about our beliefs about right and wrong: the behaviors we actually believe will be rewarded and punished.

In the end, the culture that emerges creates and motivates the behaviors which are at the root of individual and business success or failure. For Southwest, the outcomes were customer satisfaction and profitability. For Enron, the outcomes were risky transactions and ruin. But in both cases, people acted as their leaders encouraged them to behave through their own real actions.

Kelleher’s shenanigans were certainly entertaining, but it was his focus on going the extra mile for customers and cost discipline that created the loudest signal. Skilling’s lip service to risk management and code of ethics made for nice promotional videos, but he actually rewarded crazy risk-taking. And groups of humans are hard-wired to absorb these signals from authority figures and do their damnedest to conform to them.

Herb Kelleher was a bit of a wild man. And despite being the grand marshal of LUV, he definitely wasn’t a saint. Ultimately he, like Skilling and countless founders and CEOs before and after him, built his company the way only he could. Southwest’s model is well known, having been the subjects of several books countless articles; yet companies that have attempted to copy Southwest’s strategy have by and large failed. You can pretend to be someone else. But in the end, you can only be yourself.

Southwest’s culture isn’t wholly unique. There are other companies, such as Costco or The Container Store, for whom similar stories could be told. But these stories are not hagiographies—they are the stories of people who knew what they were like, and knew how to create clear cultures from their own behaviors.

Good cultures don’t have to originate with caring about people. Cultures that provide competitive advantage can be formed from many different attributes, including those often thought of negatively. For instance, transparency is en vogue in many corners of the corporate world these days, yet Phil Knight built a lively, tattooed culture based on his penchant for abrasive bluntness and secrecy. “It was a holy mission, you know, to “swoosh” the world,” stated one long-serving employee. “We were Knight’s crusaders. We would have died on the cross.”

There have been many examples of successful cultures of all different types. Many of these companies have been profiled in a wealth of articles and even best-selling books. But ultimately those books succumb to the pressures to tell leaders and HR executives how to change themselves, or how to run a canned play to match other’s performance. In the end, we just end up with more failed people and failed companies.

Those books, and the conventional wisdom about culture and business performance, miss the point. There is no one right way. There are just people being people. There are many ways for human beings to approach the world, and therefore there are many, many ways to set up a company culture.

Jeff Skilling could have built a company culture based on what he was like that would still be standing. If he had recognized his aspirations as distinct from the reality of who he was, he would have been more attuned to his blind spots. He could have designed the company in such a way that the Andy Fastow’s of the world would not have had unlimited leeway to ruin people’s lives in the name of commercial innovation. Skilling could have created clear signals through both his pronouncements and behaviors that everyone in the company understood. The various divisions and groups within the company could have amplified these signals. And those who didn’t fit in would have figured it out with much less pain.

In the end, culture is context. And context is what people are good at. No one is good at swimming in a swamp. If leaders don’t understand the integral role they play in shaping culture, and pay conscious attention to how their actions develop and nurture it, then no amount of pretty value statements and fancy market strategies will create the results they want or prevent the catastrophes they fear.

You can fly like Southwest. Or you can die like Enron. It’s really just the culture.